Today’s guest post from Ethar Alali focuses on the role (good and not so good) of health care systems and services in the climate crisis. Each post in this week’s series is intended to get us thinking ahead of our event next Tuesday 8 February. The views expressed are those of the author rather than CEM – but we welcome the provocation!

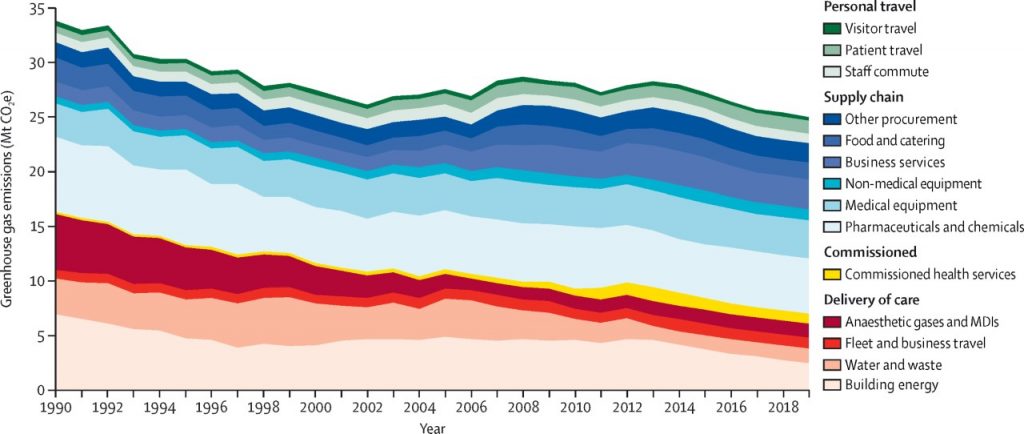

Every facet of any economy dumps its carbon impact on health and social care systems. Frontline care workers must clean up the mess of emissions from every other sector of the British economy. Yet, in the process, healthcare adds its own 25.5 million tonnes of Carbon Dioxide equivalent to some 4% to 8% of the UK total every year and causing itself £345 million in its own demand and contributing to the deaths of 36,000 people. To most, this is a horrifying realisation that healthcare indirectly causes harm. Yet, it accompanies an equally staggering realisation that solving the problem will save nearly £350 million a year in latent health demand.

Goods, services and even health products delivered through freight and logistics chains emit particulates the WHO has categorised as dangerous to human health. Exacerbating disorders like asthma, bronchitis, COPD, heatstroke and water borne disease. Depositing rubber tyre particulates in cortical matter.

As a mathematician with expertise in international socio-economic systems, I am acutely aware of how weak healthcare’s current strategic climate position is. As part of a UN team who were the first in the world to create social-accounting models to find hidden informal value networks in closed economies, understanding complex system’s “Butterfly Effects” is crucial to choosing the right strategy and in care, the right interventions.

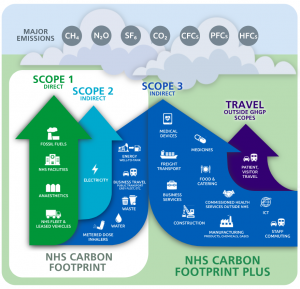

In October 2020, the NHS, battered and weary by the violence of COVID-19 and our correspondingly lacklustre public policy response, acknowledged its contribution to climate change and published its plan to tackle it. It made for pleasant reading. Greener NHS’ net zero plan acknowledged the need for system-wide change. To do more on waste, medicines, anaesthetics, and travel. It even passed references to systems thinking. The art and science of considering the service as an ecosystem of its own. Necessitating inspiration and expertise from other fields of equal or greater complexity. Yet, it remains clear that even the minds of the authors are not there yet. Leaving the health service vulnerable in its ability to deal with any upcoming tsunami of climate triggered demand as humans age, but also in how its treatments, laden with global warming potential, must be deployed with caution and captured before harm.

Climate scientists know the challenges and risks only too well. Our climate also doesn’t care what we think of it. It’s a complex, nonlinear, chaotic, cyclical relationship between life, the universe and everything. None of which can be studied in isolation. Tools the health service do not have to hand. Not in government, medical science nor public procurement, who have taken repeated policy steps in the wrong direction.

Key is the complexity science. A space where conventional medical trials offer liability not advantage. The timelines of RCTs in such contexts are unethically long while experiments remove the very coupling nonlinear complex behaviours travel over. All in the name of controlling for covariates. When those are the very essence of the relationship. Making such trial results next to useless and hampering future climate action. Thanks to decisions made in 2012 by the Medical Research Council, the UK health service is catastrophically short of people with complex systems expertise. Even rarely present in academic research. Yet, here too, our pandemic mortality levels exposed out lack of expertise. Forcing a research policy equivalent of a “woops”!

In my experience, Health services simply aren’t ready for it yet. Culturally, within its ranks, there is pressure not to be better. Despite arguably the largest active climate advocacy cohort living within it.

Yet, fields like climate science, aeronautical engineering, physics and applied mathematics offer insights into what solutions look like. Equitable, humble cooperation between these fields is essential and even means changing the way care thinks about value for money.

Health-economics, the specialist field NICE uses to evaluate each medicine and medical device, determines value for money and whether it enters the NHS supply chain. However, it has a fatal flaw. It is blindsided by climate effects and never has been. Making it blind to feedback-effects from the 439x higher GWP of the HFA propellants in Metered Dose Inhalers (MDI).Initially replacing the CFC’s of in the early 90’s, none of its downstream impacts considered at purchase. It is treated as if it has a zero impact.

For every 77,100 acute asthma related admissions every year, 64 new asthmatics can be expected from their treatment. It lasts so long, the “lifetime contribution” some 1,200 asthma cases exist each year because of it. Conventional health-economics, thinks there are none.

This is why we need a new model of evaluation. The Scottish devolved administration realise this and are considering the role health-climate-economics can play in removing blind-spot. Facilitating the eradication of cultural barriers for humble cooperation between essential actors outside the normal sphere of care.

Acknowledging their bin man is as important as your doctor, may prove to be the NHS’ hardest challenge yet. Remaining as distant an aspiration as always. Which our climate can’t afford.

Culturally, medicine may find it hard to accept the help of others with different specialities to help it change.

But change it must!

Bio: Ethar is an applied mathematician, technologist, independent researcher and author of health-climate-economics. Working with Greener NHS North West trialling a circular pharmaplastics innovation and Scottish Government offices to quantitatively consider the impact of carbon dioxide on health-economic outcomes. He has previously worked with the United nations develop programme to deliver mathematical expertise for the forensic socio-economic JOSAM toolkit for the Kingdom of Jordan

1 thought on “Why we need systems thinking when addressing the health and climate crises”